The San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site preserves the history of the most important event in Texas history — our independence from Mexico. On April 21, 1836, an outnumbered Texian Army defeated the forces of Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna on the plains of San Jacinto. With shouts of “Remember the Alamo” and “Remember Goliad,” the Texian Army secured their decisive victory in only 18 minutes!

The San Jacinto Monument, built for the battle’s centennial in 1936, honors all those who fought for Texas independence. Rising 570 feet above the surrounding plains, the Monument is the world’s tallest war memorial, standing 15 feet taller than the Washington Monument in Washington DC. A massive 220-ton Lone Star adorns the top of the towering column.

The San Jacinto Monument, built for the battle’s centennial in 1936, honors all those who fought for Texas independence. Rising 570 feet above the surrounding plains, the Monument is the world’s tallest war memorial, standing 15 feet taller than the Washington Monument in Washington DC. A massive 220-ton Lone Star adorns the top of the towering column.

Housed within the base of the Monument is the impressive San Jacinto Museum of History. This must-see museum houses thousands of objects and manuscripts that span 400 years of history. The Jesse H. Jones Theatre, also housed in the base of the Monument, features a short video on Texas history.

Housed within the base of the Monument is the impressive San Jacinto Museum of History. This must-see museum houses thousands of objects and manuscripts that span 400 years of history. The Jesse H. Jones Theatre, also housed in the base of the Monument, features a short video on Texas history.

I especially enjoyed the 500-foot elevator ride to the observation deck that sits beneath the Lone Star of Texas at the top of the Monument. The observation deck offers great views of the surrounding area as well as of Battleship Texas. Information panels at each window help to orient and inform you about the surrounding vistas.

I especially enjoyed the 500-foot elevator ride to the observation deck that sits beneath the Lone Star of Texas at the top of the Monument. The observation deck offers great views of the surrounding area as well as of Battleship Texas. Information panels at each window help to orient and inform you about the surrounding vistas.

This historic site is sacred ground in Texas — and rightly so. The Texas Veterans Association and the Sons and Daughters of the Republic of Texas helped to raise the money to purchase the land and to build the Monument. Prominent Houstonian Jesse H. Jones, who served as President Roosevelt’s Secretary of Commerce, also aided in the development of the historic site.

This historic site is sacred ground in Texas — and rightly so. The Texas Veterans Association and the Sons and Daughters of the Republic of Texas helped to raise the money to purchase the land and to build the Monument. Prominent Houstonian Jesse H. Jones, who served as President Roosevelt’s Secretary of Commerce, also aided in the development of the historic site.

The San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site is located in La Porte, just a short drive from Houston. The Monument and Museum are open daily (except for Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, and Christmas Day) from 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM. The museum is free to all visitors but there is a modest charge to see the movie and to ride the elevator to the observation floor. When you visit, plan also to tour Battleship Texas, located just a minute or two by car from the Monument.

The San Jacinto Battleground State Historic Site is located in La Porte, just a short drive from Houston. The Monument and Museum are open daily (except for Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, and Christmas Day) from 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM. The museum is free to all visitors but there is a modest charge to see the movie and to ride the elevator to the observation floor. When you visit, plan also to tour Battleship Texas, located just a minute or two by car from the Monument.

Texas History

Battleship Texas State Historic Site

There is a great line about history in Timeline, Michael Crichton’s science fiction novel about a group of history students who travel back in time to rescue their professor from 14th century France. One of the time-traveling students says, “Professor Johnston often said that if you didn’t know history, you didn’t know anything. You were a leaf that didn’t know it was part of a tree.”

I absolutely agree! Knowing history is important for a lot of reasons, not the least of which is to understand the context in which we live and how our lives fit into a larger narrative. When you think about it, our way of life is linked to the actions, good and bad, of those who came before us. History helps us to make sense of it all.

Texas is indeed rich in history and blessed with historic sites throughout the state. These sites help preserve the fascinating history of the Lone Star State for our benefit and that of future generations. The Battleship Texas State Historic Site is one of my favorites. Battleship Texas, last of the world’s dreadnoughts, is permanently moored on Buffalo Bayou near the San Jacinto State Battleground Historic Site in La Porte.

Texas is indeed rich in history and blessed with historic sites throughout the state. These sites help preserve the fascinating history of the Lone Star State for our benefit and that of future generations. The Battleship Texas State Historic Site is one of my favorites. Battleship Texas, last of the world’s dreadnoughts, is permanently moored on Buffalo Bayou near the San Jacinto State Battleground Historic Site in La Porte.

Battleship Texas was commissioned on March 12, 1914. Once the most powerful weapon in the world, it is the only surviving battleship to have served in both world wars. Before the second world war, USS Texas became flagship of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet. In World War 2, this big-gun battleship played a key role in bombing Nazi defenses in Normandy on D-Day. And, in all of her years of service through two world wars, the ship suffered only one combat fatality.

Battleship Texas was commissioned on March 12, 1914. Once the most powerful weapon in the world, it is the only surviving battleship to have served in both world wars. Before the second world war, USS Texas became flagship of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet. In World War 2, this big-gun battleship played a key role in bombing Nazi defenses in Normandy on D-Day. And, in all of her years of service through two world wars, the ship suffered only one combat fatality.

After her service, Battleship Texas was scheduled to be used as a bombing target. However, thanks to efforts on the part of some history-minded Texans, the ship was saved. The Navy towed the USS Texas from Hawkins Point, Baltimore to its present location along Houston’s ship channel to become the nation’s first permanent memorial battleship. She was officially transferred to the state in ceremonies at San Jacinto Battleground on April 21, 1948. That date is important because in 1836, Texans won the battle for Texas independence on April 21 at the Battle of San Jacinto.

After her service, Battleship Texas was scheduled to be used as a bombing target. However, thanks to efforts on the part of some history-minded Texans, the ship was saved. The Navy towed the USS Texas from Hawkins Point, Baltimore to its present location along Houston’s ship channel to become the nation’s first permanent memorial battleship. She was officially transferred to the state in ceremonies at San Jacinto Battleground on April 21, 1948. That date is important because in 1836, Texans won the battle for Texas independence on April 21 at the Battle of San Jacinto.

Today, this historic site is maintained by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. The site is open seven days a week from 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM with the exception of Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, and Christmas Day. Park personnel and volunteers are onboard the ship and available to answer questions or to guide you through the upper and lower decks. Believe me when I tell you that this is one fascinating tour.

Today, this historic site is maintained by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. The site is open seven days a week from 10:00 AM to 5:00 PM with the exception of Thanksgiving, Christmas Eve, and Christmas Day. Park personnel and volunteers are onboard the ship and available to answer questions or to guide you through the upper and lower decks. Believe me when I tell you that this is one fascinating tour.

As you consider interesting things to do in the Lone Star State, make it a point to included a visit to Battleship Texas State Historic Site. You will definitely learn some new and interesting things. And you will walk away with a greater appreciation for those who served aboard this mighty ship that played a key role in helping to preserve our democratic way of life.

As you consider interesting things to do in the Lone Star State, make it a point to included a visit to Battleship Texas State Historic Site. You will definitely learn some new and interesting things. And you will walk away with a greater appreciation for those who served aboard this mighty ship that played a key role in helping to preserve our democratic way of life.

Founders Memorial Cemetery

Cemeteries, with few exceptions, do not rank high on lists of places to visit. But, perhaps they should. Cemeteries, after all, are the resting places of those who, to whatever degree, have influenced the course of our own lives. If we look back and connect the dots, then the dots in our respective stories will eventually lead us back to a cemetery — perhaps to the grave of a family member or a friend or some historical figure whose life had a far-reaching impact.

The Founders Memorial Cemetery is the oldest burial ground in Houston and certainly one of the most interesting. Dedicated by the city as a memorial park in 1836, this tranquil two-acre cemetery is the final resting place of several figures important to the history of Houston and the Lone Star State. A marker at the cemetery notes: “This park is dedicated to the men and women — many of whom sleep here — who founded and defended the Republic of Texas. May they rest in peace”

The Founders Memorial Cemetery is the oldest burial ground in Houston and certainly one of the most interesting. Dedicated by the city as a memorial park in 1836, this tranquil two-acre cemetery is the final resting place of several figures important to the history of Houston and the Lone Star State. A marker at the cemetery notes: “This park is dedicated to the men and women — many of whom sleep here — who founded and defended the Republic of Texas. May they rest in peace”

The land for the cemetery was donated by the Allen Brothers in 1836, the same year these brothers founded the city of Houston. In those years the cemetery was located at the outskirts of town. Today, it is surrounded by skyscrapers and adjacent to Rose of Sharon Missionary Baptist Church in Houston’s Fourth Ward — once known as Freedman’s Town, a community originally settled by freed slaves.

The land for the cemetery was donated by the Allen Brothers in 1836, the same year these brothers founded the city of Houston. In those years the cemetery was located at the outskirts of town. Today, it is surrounded by skyscrapers and adjacent to Rose of Sharon Missionary Baptist Church in Houston’s Fourth Ward — once known as Freedman’s Town, a community originally settled by freed slaves.

No one knows for sure how many people are buried in this old cemetery. The city did not maintain the best of burial records in its very early days. According to a conservative estimate, there may be as many as 850 graves at the site. During the yellow fever and cholera epidemics of the 1850s, many people died and were quickly interred, some in mass graves. What we do know is that there are approximately eighty headstones at the cemetery, many so weather-beaten that their epitaphs are indecipherable.

No one knows for sure how many people are buried in this old cemetery. The city did not maintain the best of burial records in its very early days. According to a conservative estimate, there may be as many as 850 graves at the site. During the yellow fever and cholera epidemics of the 1850s, many people died and were quickly interred, some in mass graves. What we do know is that there are approximately eighty headstones at the cemetery, many so weather-beaten that their epitaphs are indecipherable.

There are 28 Texas Centennial Monuments at the cemetery, more than in any other cemetery in Texas except the State Cemetery in Austin. These mark the graves of veterans of the Battle of San Jacinto, dignitaries who served the Republic of Texas, prominent pioneer families and Houston citizens, John Kirby Allen who co-founded Houston, the mother of Republic of Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar, and a signer a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence.

There are 28 Texas Centennial Monuments at the cemetery, more than in any other cemetery in Texas except the State Cemetery in Austin. These mark the graves of veterans of the Battle of San Jacinto, dignitaries who served the Republic of Texas, prominent pioneer families and Houston citizens, John Kirby Allen who co-founded Houston, the mother of Republic of Texas President Mirabeau B. Lamar, and a signer a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence.

Founders Memorial Cemetery is located just west of downtown Houston at 1217 West Dallas. The entrance is located at the intersection of West Dallas and Valentine Street. The memorial park is maintained by the Houston Parks and Recreation Department and is open from dawn to dusk. If you are planning to visit the San Jacinto Monument or other historical sites in the greater Houston area, then add this cemetery to your list. Walk slowly and respectfully among the graves of those who helped shape the history of the Lone Star State.

Founders Memorial Cemetery is located just west of downtown Houston at 1217 West Dallas. The entrance is located at the intersection of West Dallas and Valentine Street. The memorial park is maintained by the Houston Parks and Recreation Department and is open from dawn to dusk. If you are planning to visit the San Jacinto Monument or other historical sites in the greater Houston area, then add this cemetery to your list. Walk slowly and respectfully among the graves of those who helped shape the history of the Lone Star State.

Don Pedrito Jaramillo

Known as the Healer of Los Olmos and the Saint of Falfurrias, Don Pedrito Jaramillo remains highly regarded by folks in South Texas. He was born to Indian parents sometime around 1829 in Guadalajara, Mexico. After the death of his mother in 1881, Jaramillo moved to the Los Olmos Ranch near present-day Falfurrias.

According to legend, this poor Mexican laborer fell off his horse and broke his nose while working as a cowboy on the Los Olmos Ranch. The pain of his injury kept him awake for several days. When he was finally able to sleep, he was told by God in a dream that he had been given the gift to heal people.

According to legend, this poor Mexican laborer fell off his horse and broke his nose while working as a cowboy on the Los Olmos Ranch. The pain of his injury kept him awake for several days. When he was finally able to sleep, he was told by God in a dream that he had been given the gift to heal people.

Don Pedrito, as he affectionately came to be known, started treating the sick and injured who lived on the surrounding ranches. He quickly earned a reputation as a curandero, the Spanish word for healer. Curanderos are a part of the rich texture of Hispanic culture in Texas. In days when doctors were few and far between and folks had little money to pay a physician, curanderos offered palliative solutions and cures to the poor.

Don Pedrito, as he affectionately came to be known, started treating the sick and injured who lived on the surrounding ranches. He quickly earned a reputation as a curandero, the Spanish word for healer. Curanderos are a part of the rich texture of Hispanic culture in Texas. In days when doctors were few and far between and folks had little money to pay a physician, curanderos offered palliative solutions and cures to the poor.

Don Pedrito’s cures included mud packs (what he had used when he broke his nose), various poultices, herbal plants, and drinking large quantities of water. The compassionate healer often provided what he prescribed to his impoverished patients. His cures were so effective that people from throughout the region and, reportedly, from as far away as New York sought him out. In the years before easy access to medical care, Don Pedrito was to the folks of his day what dialing 9-1-1 and emergency rooms are to us today.

Don Pedrito’s cures included mud packs (what he had used when he broke his nose), various poultices, herbal plants, and drinking large quantities of water. The compassionate healer often provided what he prescribed to his impoverished patients. His cures were so effective that people from throughout the region and, reportedly, from as far away as New York sought him out. In the years before easy access to medical care, Don Pedrito was to the folks of his day what dialing 9-1-1 and emergency rooms are to us today.

Although Don Pedrito never charged for his services, he regularly received unsolicited donations. He gave much of this money to local churches and kept some on hand to fund a large food pantry to help people in need. By some reports, Don Pedrito would spend hundreds of dollars at a time to buy food to give away. When he died in 1907, he still had more than $5,000 in 50-cent pieces set aside for his philanthropic work.

Today, more than a hundred years after his death, the faithful and the curious continue to visit the shrine of this South Texas folk saint — his final resting place. The whitewashed interior walls of the modest building are adorned with handwritten notes and photos of those either seeking help or who claim to have been helped or healed as a result of their visit to the shrine of Don Pedrito. Don, by the way, was not Pedro Jaramillo’s first name. Don is a title of esteem and respect in the Hispanic community.

Today, more than a hundred years after his death, the faithful and the curious continue to visit the shrine of this South Texas folk saint — his final resting place. The whitewashed interior walls of the modest building are adorned with handwritten notes and photos of those either seeking help or who claim to have been helped or healed as a result of their visit to the shrine of Don Pedrito. Don, by the way, was not Pedro Jaramillo’s first name. Don is a title of esteem and respect in the Hispanic community.

The shrine is open daily from sunup to sunset. To get to the shrine, take Highway 285 east out of Falfurrias and look for the sign pointing the way just before you get to FM 1418. The shrine is located two miles north of Highway 285 on your right. Everyone is welcome. The curio shop next door sells candles, herbs, incense, and snacks.

The shrine is open daily from sunup to sunset. To get to the shrine, take Highway 285 east out of Falfurrias and look for the sign pointing the way just before you get to FM 1418. The shrine is located two miles north of Highway 285 on your right. Everyone is welcome. The curio shop next door sells candles, herbs, incense, and snacks.

Regardless of your own spiritual beliefs, take a quick detour to visit the shrine if you happen to be in the area to see the place where a poor Mexican laborer earned a widespread reputation as a beloved curandero. The story of this South Texas folk saint is, after all, a part of our rich Texas history.

John Henry Faulk’s Christmas Story

Everybody loves a good story — a real or imaginary account that captures our imagination and transports us to another place or time. That’s what would happen every time my grandfather would tell me a story. The sound of his voice, the subtle inflection of a word, a phrase told in a rising crescendo or trailing off into a whisper. He used these tools of the storyteller to mesmerize me — to unlock the door to my soul where his stories ultimately took up residence.

A few years ago I became acquainted with another storyteller whose masterful delivery also captured my imagination. John Henry Faulk, the fourth of five children, was born in Austin in 1913 and would become one of the Lone Star State’s most beloved storytellers. He was deeply influenced by his freethinking Methodist parents who taught him to detest racism. His post-graduate thesis at the University of Texas was about the civil rights abuses faced by African-Americans.

Faulk honed his storytelling abilities while teaching English at the University of Texas and later as a Merchant Marine during the Second World War. His friend Alan Lomax, who worked at the CBS network in New York, hosted several parties during Christmas 1945 to introduce his radio broadcasting friends to Faulk’s yarn-spinning abilities. A few months later, CBS gave Faulk his own weekly radio program, providing him with the thing every storyteller craves — an audience.

Faulk honed his storytelling abilities while teaching English at the University of Texas and later as a Merchant Marine during the Second World War. His friend Alan Lomax, who worked at the CBS network in New York, hosted several parties during Christmas 1945 to introduce his radio broadcasting friends to Faulk’s yarn-spinning abilities. A few months later, CBS gave Faulk his own weekly radio program, providing him with the thing every storyteller craves — an audience.

Sadly, Faulk’s radio career was derailed in 1957 when he became a victim of Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy’s witch hunt for Communist sympathizers. The blacklisted storyteller, however, fought back. With support from famed broadcast journalist Edward R. Murrow, Faulk won a libel suit against those who had tarnished his reputation. The jury, in fact, awarded him the largest libel judgement in history to that date. In 1963, Faulk chronicled his experience in his book Fear on Trial. CBS television broadcast its movie version of Faulk’s story in 1974.

In his latter years, Faulk made numerous appearances as a homespun character on the popular Hee-Haw television program. He also wrote two one-man plays — Deep in the Heart and Pear Orchard, Texas. Throughout the 1980s he was a popular speaker on college campuses, speaking often on the freedoms guaranteed by the First Amendment. On April 9, 1990, Faulk died of cancer in his hometown of Austin. The city of Austin later named the downtown branch of the public library in his honor.

A few years ago on a dark December night, while traveling to my hometown for Christmas, I tuned in to National Public Radio and heard a story that touched me deeply. The story was one that John Henry Faulk had recorded in 1974 for the program Voices in the Wind. NPR later rebroadcast Faulk’s story in 1994. Every year since then, NPR has rebroadcast Faulk’s heartwarming Christmas Story. This story has earned a place among my favorite Christmas stories and movies. I listen to it every year at Christmas.

I encourage you to take a few minutes to listen to John Henry Faulk’s Christmas Story. Gather your family around and invite them to listen as well. But, be warned. Faulk’s homespun story will mesmerize you. The sound of his voice will transport you back to simpler days before Christmas came under fire. I think you will agree that the Lone Star State produced a great storyteller in John Henry Faulk and that his Christmas story should be heard by a new generation. Best wishes for the most wonderful Christmas ever.

I encourage you to take a few minutes to listen to John Henry Faulk’s Christmas Story. Gather your family around and invite them to listen as well. But, be warned. Faulk’s homespun story will mesmerize you. The sound of his voice will transport you back to simpler days before Christmas came under fire. I think you will agree that the Lone Star State produced a great storyteller in John Henry Faulk and that his Christmas story should be heard by a new generation. Best wishes for the most wonderful Christmas ever.

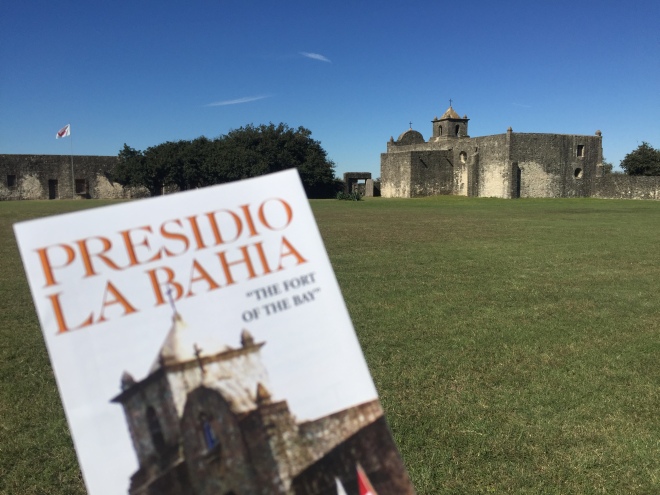

Presidio La Bahia

Presidio La Bahia, the world’s finest example of a Spanish frontier fort, is located outside the town of Goliad. The original fort was built in 1721 on the banks of Garcitas Creek near present day Port Lavaca. When this location proved unsuitable, the fort was moved inland in 1726 to a location near present day Victoria. In 1749, the fort was again relocated to its present location near the banks of the San Antonio River.

Presidio La Bahia was responsible for the defense of the coastal area and eastern province of Texas. Within time, a settlement called La Bahia (The Bay) grew up around the fort. The name of La Bahia was changed to Goliad in 1829 in honor of Father Miguel Hidalgo, the patriot priest of the Mexican Revolution. Goliad is an anagram formed from the letters of the name Hidalgo (minus the silent letter H).

Presidio La Bahia was responsible for the defense of the coastal area and eastern province of Texas. Within time, a settlement called La Bahia (The Bay) grew up around the fort. The name of La Bahia was changed to Goliad in 1829 in honor of Father Miguel Hidalgo, the patriot priest of the Mexican Revolution. Goliad is an anagram formed from the letters of the name Hidalgo (minus the silent letter H).

On October 9, 1835, Captain George Collinsworth and his band of Texas fighters attacked and defeated the Mexican garrison stationed at the Presidio. On December 20 of that year, the first Declaration of Texas Independence was formally declared at the fort. This Declaration was signed by 92 Texas citizens inside the chapel of Our Lady of Loreto, the oldest building in the compound.

On October 9, 1835, Captain George Collinsworth and his band of Texas fighters attacked and defeated the Mexican garrison stationed at the Presidio. On December 20 of that year, the first Declaration of Texas Independence was formally declared at the fort. This Declaration was signed by 92 Texas citizens inside the chapel of Our Lady of Loreto, the oldest building in the compound.

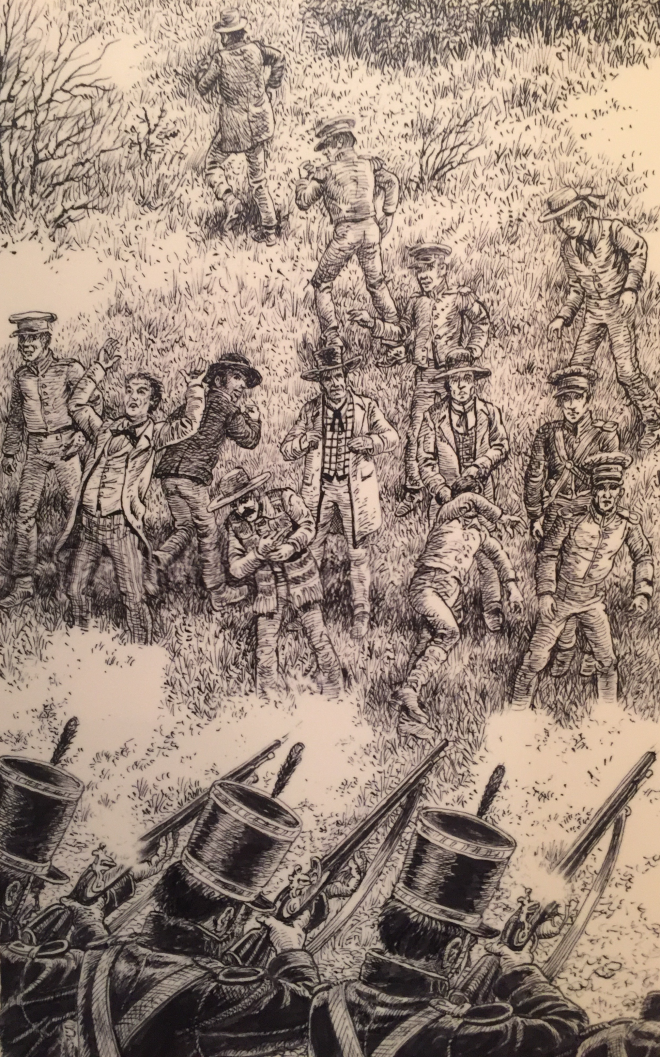

The darkest day in Texas history, the Goliad Massacre, took place at Presidio La Bahia on March 27, 1836 — Palm Sunday. Colonel James Walker Fannin and 341 men under his command had surrendered to General José de Urrea of the Mexican army on March 20 at the Battle of Coleto Creek. The Mexican army held Fannin and his men as prisoners at the Presidio and at the chapel of Our Lady of Loreto.

The darkest day in Texas history, the Goliad Massacre, took place at Presidio La Bahia on March 27, 1836 — Palm Sunday. Colonel James Walker Fannin and 341 men under his command had surrendered to General José de Urrea of the Mexican army on March 20 at the Battle of Coleto Creek. The Mexican army held Fannin and his men as prisoners at the Presidio and at the chapel of Our Lady of Loreto.

Fannin and his men had drafted terms of surrender and expected to be treated with a measure of dignity as prisoners of war. General Urrea, however, told Fannin that he could not ratify his terms. He was bound by Santa Anna’s orders and a congressional decree to accept no terms other than unconditional surrender. And, although General Urrea recommended clemency for Fannin and his men, he later received orders from Santa Anna to execute all of the prisoners. He was left with no choice but to carry out the orders.

Fannin and his men had drafted terms of surrender and expected to be treated with a measure of dignity as prisoners of war. General Urrea, however, told Fannin that he could not ratify his terms. He was bound by Santa Anna’s orders and a congressional decree to accept no terms other than unconditional surrender. And, although General Urrea recommended clemency for Fannin and his men, he later received orders from Santa Anna to execute all of the prisoners. He was left with no choice but to carry out the orders.

Some of the men were killed on the grounds of the Presidio and others were killed outside the fort. A few managed to escape. Twice as many men died at the Goliad Massacre than died at the Alamo. As news of the Goliad Massacre spread, streams of volunteers came to Texas to take up arms against the brutal dictator Santa Anna. “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” became the most potent battle cries of the Texas Revolution.

Some of the men were killed on the grounds of the Presidio and others were killed outside the fort. A few managed to escape. Twice as many men died at the Goliad Massacre than died at the Alamo. As news of the Goliad Massacre spread, streams of volunteers came to Texas to take up arms against the brutal dictator Santa Anna. “Remember the Alamo!” and “Remember Goliad!” became the most potent battle cries of the Texas Revolution.

Fannin and his men are buried in a mass grave outside of the walls of the Presidio. Their names are etched on the pink granite walls of the Fannin Memorial Monument, erected over the burial site in 1938 by the State of Texas. This site is located next to La Bahia Cemetery where you can find grave markers that date back to the mid-nineteenth century.

Fannin and his men are buried in a mass grave outside of the walls of the Presidio. Their names are etched on the pink granite walls of the Fannin Memorial Monument, erected over the burial site in 1938 by the State of Texas. This site is located next to La Bahia Cemetery where you can find grave markers that date back to the mid-nineteenth century.

Our Lady of Loreto Chapel, where Fannin and his men spent their final days, is one of the oldest churches in the United States and is still in use today. In 1946, Antonio Garcia of Corpus Christi, known as the “Michelangelo of South Texas,” painted a beautiful fresco behind the altar. Lincoln Borglum, son of Gutzon Borglum of Mount Rushmore fame, sculpted the statue of Our Lady of Loreto that sits in the outside niche above the doors to the chapel.

Our Lady of Loreto Chapel, where Fannin and his men spent their final days, is one of the oldest churches in the United States and is still in use today. In 1946, Antonio Garcia of Corpus Christi, known as the “Michelangelo of South Texas,” painted a beautiful fresco behind the altar. Lincoln Borglum, son of Gutzon Borglum of Mount Rushmore fame, sculpted the statue of Our Lady of Loreto that sits in the outside niche above the doors to the chapel.

You can learn much more about the history of Presidio La Bahia by visiting this National Historic Landmark. Visitors should watch the brief video that gives a broad overview of the history of the fort before walking through the museum filled with artifacts found on site. The grounds and out buildings are well-maintained and give visitors a sense of what life was like at the Presidio.

You can learn much more about the history of Presidio La Bahia by visiting this National Historic Landmark. Visitors should watch the brief video that gives a broad overview of the history of the fort before walking through the museum filled with artifacts found on site. The grounds and out buildings are well-maintained and give visitors a sense of what life was like at the Presidio.

As you travel the Lone Star State, be sure to visit the sites that preserve the history of the Texas Revolution. Visiting Presidio La Bahia and the Fannin Memorial Monument in Goliad is a great way to remember and honor those who gave their lives for the great state of Texas. Their sacrifice should not be forgotten.

As you travel the Lone Star State, be sure to visit the sites that preserve the history of the Texas Revolution. Visiting Presidio La Bahia and the Fannin Memorial Monument in Goliad is a great way to remember and honor those who gave their lives for the great state of Texas. Their sacrifice should not be forgotten.

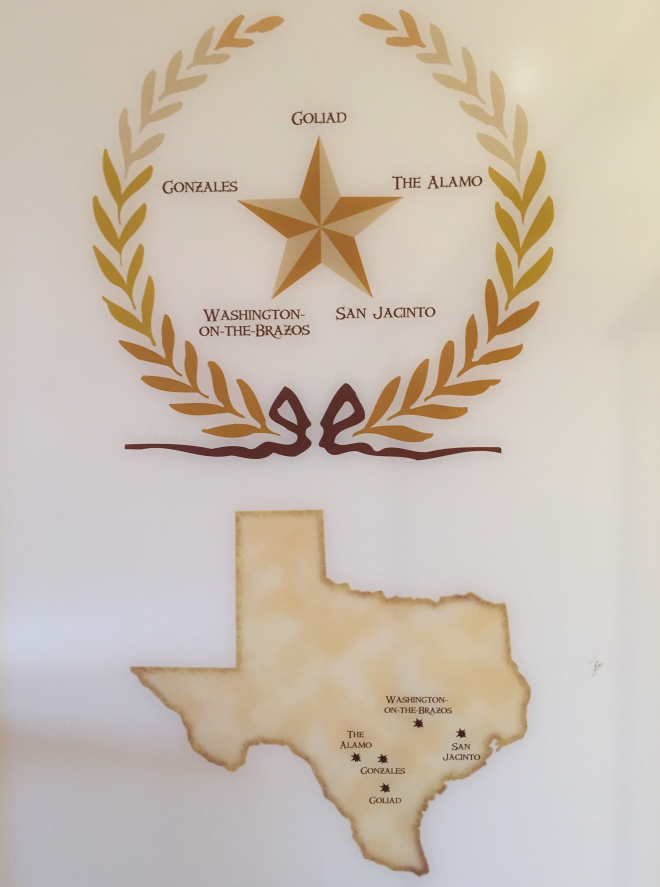

A Texas History Road Trip

Something good happens when you combine book learning with field trips — somehow the things and events that happened in a particular place seem to make more sense. I am a firm believer that being onsite can help folks to gain greater insight. Being in the geographical context of history’s happenings stirs the imagination, stimulates brain activity, promotes conversation, and inspires wonder.

Last week, my friend Brad Flurry and his sons Hunter and Drew joined me for a Texas History road trip. Since we only had a few hours before the boys had to be at football practice, I planned a route to two locations along the Brazos River — San Felipe de Austin and Washington-on-the-Brazos. San Felipe is regarded as the “Cradle of Texas Liberty” and Washington-on-the-Brazos is the place where Texas became Texas.

Before visiting San Felipe, we drove to a spot where the boys could walk down to the Brazos River. This was the perfect setting for talking about the Lone Star State’s longest river, including how it got its name and the role it played in promoting commerce in the early days of Texas. And, of course, it was also a good spot for chucking a few rocks into the river.

Before visiting San Felipe, we drove to a spot where the boys could walk down to the Brazos River. This was the perfect setting for talking about the Lone Star State’s longest river, including how it got its name and the role it played in promoting commerce in the early days of Texas. And, of course, it was also a good spot for chucking a few rocks into the river.

San Felipe was the unofficial capital of the colony that Stephen F. Austin founded at this site in 1823. Today, the folks at the San Felipe State Historic Site, a Texas Historical Commission property, guide visitors in understanding the significance of the many historical events that occurred in this community. The site features a hand-dug water well from the period, a museum, and a replica of an old cabin with toys and games from the period.

From San Felipe we drove an hour north to Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site. This is the place where Texas became Texas. In March of 1836, while the Alamo was under siege by Santa Anna’s army, 59 representatives of the Texas settlements met in an unfinished frame building at Washington to make a formal declaration of independence from Mexico. A replica of this building, known as Independence Hall, marks the place where the Texas Declaration of Independence was signed.

From San Felipe we drove an hour north to Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site. This is the place where Texas became Texas. In March of 1836, while the Alamo was under siege by Santa Anna’s army, 59 representatives of the Texas settlements met in an unfinished frame building at Washington to make a formal declaration of independence from Mexico. A replica of this building, known as Independence Hall, marks the place where the Texas Declaration of Independence was signed.

From Independence Hall we hiked to a scenic overlook of the Brazos River and talked about the Runaway Scrape of 1836. As Santa Anna’s armies swept eastward from San Antonio, panic set in among the settlements of Texas. Colonists gathered personal possessions, abandoned their properties and headed eastward under difficult conditions. Settlers often waited days to cross the Brazos at Washington. After the Texas victory at the Battle of San Jacinto, settlers slowly returned to their homes.

From Independence Hall we hiked to a scenic overlook of the Brazos River and talked about the Runaway Scrape of 1836. As Santa Anna’s armies swept eastward from San Antonio, panic set in among the settlements of Texas. Colonists gathered personal possessions, abandoned their properties and headed eastward under difficult conditions. Settlers often waited days to cross the Brazos at Washington. After the Texas victory at the Battle of San Jacinto, settlers slowly returned to their homes.

To stand at the very spot where the Texas Declaration of Independence was signed or where something like the Runaway Scrape occurred does indeed stir the imagination. And, that’s a good thing! It’s far to easy for us to live disconnected from the past, unaware of how and why we are the beneficiaries of the courage and the sacrifices of those who came before us. The best antidote to that is to personally visit the places that shaped our history.

There are no shortages of affordable day trips from wherever you live in Texas that can help you and your kids gain a greater appreciation for the history of the Lone Star State. I hope you’ll hit the road soon and embark on a Texas history road trip.

The Brazos River

The Brazos is the longest river in the Lone Start State and one rich in history. The name of this 840-mile long waterway comes from the Spanish word for “arms.” Early Spanish explorers named this wide and slow-moving river Rio de Los Brazos de Dios — translated “The Arms of God River.”

There are several legends about how the Brazos got its name. However, the common denominator among these stories is that thirsty explorers happened upon the river in the nick of time and were refreshed by its waters. These intrepid souls felt as though they had stumbled into the arms of God and were saved!

There are several legends about how the Brazos got its name. However, the common denominator among these stories is that thirsty explorers happened upon the river in the nick of time and were refreshed by its waters. These intrepid souls felt as though they had stumbled into the arms of God and were saved!

San Felipe de Austin, founded in 1824 by Stephen F. Austin, was the first permanent settlement along the Brazos River. Located on a high and easily defensible bluff near the Brazos River, San Felipe became the unofficial capital of Austin’s colony. The town was later incorporated in 1837 and became the county seat of the newly established Austin County.

The nearby town of Washington, also known as Washington-on-the-Brazos, is recognized as the birthplace of Texas. It’s where Texas became Texas. On March 2, 1836, fifty-nine delegates met at Washington to make a formal declaration of independence from Mexico and birthed the Republic of Texas. Today, visitors to the Washington-on-the Brazos State Historic Site can walk through Independence Hall, the simple frame building where the fate of Texas was determined.

The nearby town of Washington, also known as Washington-on-the-Brazos, is recognized as the birthplace of Texas. It’s where Texas became Texas. On March 2, 1836, fifty-nine delegates met at Washington to make a formal declaration of independence from Mexico and birthed the Republic of Texas. Today, visitors to the Washington-on-the Brazos State Historic Site can walk through Independence Hall, the simple frame building where the fate of Texas was determined.

In the early years of Texas, the Brazos River was navigable from the Gulf all the way to Washington. Today, canoeists and kayakers enjoy paddling the slow flat waters of the historic Brazos River. Over the past few years I have enjoyed paddling on the Brazos as well as just relaxing on its banks as it flows past Stephen F. Austin and Brazos Bend State Parks. These parks afford bikers and hikers some exceptional views of the Brazos.

In the early years of Texas, the Brazos River was navigable from the Gulf all the way to Washington. Today, canoeists and kayakers enjoy paddling the slow flat waters of the historic Brazos River. Over the past few years I have enjoyed paddling on the Brazos as well as just relaxing on its banks as it flows past Stephen F. Austin and Brazos Bend State Parks. These parks afford bikers and hikers some exceptional views of the Brazos.

The next time you drive across Texas and cross over the Brazos, take a moment to reflect on the long and rich history of the longest waterway in the Lone Star State. If you have time, visit one of the parks near the river and bike or hike the trails that overlook this magnificent waterway. And be sure to slow down and make time to relax, reflect, and enjoy the quiet when you visit the Brazos. Enjoy the embrace of Los Brazos de Dios.

The next time you drive across Texas and cross over the Brazos, take a moment to reflect on the long and rich history of the longest waterway in the Lone Star State. If you have time, visit one of the parks near the river and bike or hike the trails that overlook this magnificent waterway. And be sure to slow down and make time to relax, reflect, and enjoy the quiet when you visit the Brazos. Enjoy the embrace of Los Brazos de Dios.

Record Your Own Texas History

I have always enjoyed going home — back to the places where my childhood memories were made. On a recent trip to visit my Dad, I listened to a 2-hour taped interview between my uncle and my grandfather. This recording was made on January 15, 1975. The cassette had been tucked away for years for safe keeping. As soon as my grandfather started speaking, memories flooded the room and engulfed me in waves of pensive emotions.

The interview was fascinating. My grandfather talked a lot about his family. He told the story of returning to his mother’s home to visit his grandfather. While there, his grandfather died. So, he negotiated with the local blacksmith, who also had carpentry skills, to have a coffin made and then arranged for his grandfather’s burial. He also spoke about his first school teacher and classmates and what life was like growing up on a ranch.

I especially liked his story about traveling from the family ranch near San Diego, Texas all the way to California in 1917. My grandfather talked about the route and how difficult it was to drive on the poor and sometimes impassable roads in those days before any highways or the interstate highway system. And when he arrived in Hollywood he learned that they were filming a western and applied to be an extra since he was a skilled cowboy.

One of the most riveting parts of the interview was the time he served as an election judge in Duval Country, known for its political intrigue. When a particular election did not go as some in power had hoped, two police officers were sent to arrest him and take the ballot boxes from him before he could get them to the county courthouse. My grandfather did not give up the ballot boxes, asked to see the warrant for his arrest (none was offered), and succeeded in getting the voting results to the courthouse. He was never arrested.

I loved every story he told, including the account of marrying my grandmother, starting the first Boy Scout troop for Hispanics in Duval Country and later in the Rio Grande Valley, enlisting in the First World War, and so many other great stories. Had my uncle not interviewed my grandfather, all of these wonderful memories would have been buried with him. And although I had heard some of these stories when I was a kid, it was good to hear them again as an adult. I appreciate them so much more. They are treasures. They are a part of the history of my family.

I believe in the importance of recording family history lest it fade from memory, never to be seen or heard again. In this day of digital devices, there are no good excuses for failing to be a family historian. Here are a few practical suggestions for recording your family’s Texas history.

Interviews | Interview your grandparents and parents. Ask them to share stories about their childhood and your family that you can share with your children. If possible, interview them at a place that will awaken dormant memories.

Photographs | Sit with your family’s elders and ask them to tell you the stories associated with old photographs. Record the stories and names of the people in the photographs. Use a photo service to create photo books that can be easily reproduced and shared with family members.

Technology | Record interviews on video and audio devices. Ask family members specific questions about your family’s history. Be sure to ask them about how they responded to key events like the Kennedy assassination or the lunar landing.

Holidays | Use holidays, reunions, and other times when your family gathers together as a time to talk with older family members and to record some of your family’s history. Talk about traditions, vacations, celebrations, and getting through hard times together.

Journal | Don’t neglect to record your own history in a journal or even on a blog. By doing so you will ensure that your own kids will have access to your story.